By Tom Jarvis and Scott Merrill

A crime that only takes a few seconds or minutes – a murder committed in the heat of the moment, an armed robbery – can lead to years in the New Hampshire criminal justice system. And for those facing potentially long prison sentences, the first months of incarceration can be some of the cruelest, especially for those unfamiliar with the system.

The initial shock of being in jail after an arrest, staying there while awaiting a sentence hearing, and then entering the prison system and going through Reception and Diagnostics (R&D) presents a gauntlet of psychological and social challenges. Separated from family while awaiting hearings and sentencing, learning to perfect one’s “chow-hall face,” and accepting – or not – a loss of autonomy, the newly incarcerated must come to terms with their circumstances and the consequences of their crimes.

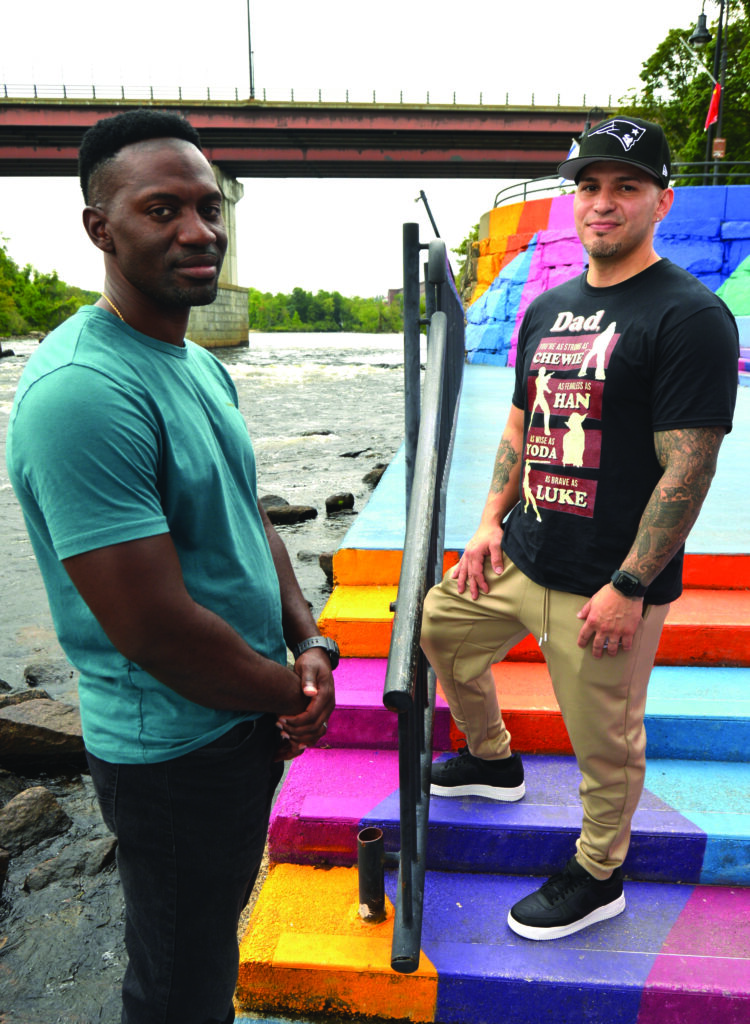

Former New Hampshire State Prison inmates, Tony Hebert and Evenor Pineda (left) and Joseph Lascaze with Pineda (right), near Arms Park in Manchester. Photos by Scott Merrill

Joseph Lascaze was first introduced to the criminal justice system after an arrest for armed robbery in 2005 at the age of 17 and served time in various New Hampshire prisons for more than 13 years. He says the initial days and months at the county jail were one blunt reminder after another that his life was never going to be the same. He recalls his time at the Hillsborough County House of Corrections (locally known as the Valley Street Jail) in Manchester – where he awaited sentencing for 13 months before entering the state prison following a plea deal – as the worst experience of his life.

“I’d rather do five years in prison than a year at Valley Street,” Lascaze says. “It was absolutely terrible.”

Awaiting Sentencing

Defendants awaiting sentencing after being found guilty of felonies, or those awaiting plea hearings – like Lascaze – are remanded by a judge to one of the county jails. Any days the defendant serves in the county facility count toward the prison sentence, with some exceptions.

One of those exceptions is when a defendant is arrested on two charges at the same time and is held in jail pending trial or plea on both. In this case, a judge may decide to only award what is usually called “pre-trial credit” toward one of the charges.

“The law is that a defendant may not ‘double dip,’ which refers to a defendant getting his time awaiting a disposition to more than one charge,” says Donna Brown, an attorney who worked for New Hampshire Public Defender for 25 years before going into private practice. “A judge has the discretion to award the pre-credit on multiple charges, [but] the defendant is not entitled to ‘double dip.’”

In some cases, if the defendant was already out on bail during the trial, the judge may allow them to remain out pending sentencing. But this wasn’t an option for Lascaze, who was unable to post the $100,000 bail the State had set. This was common for most people at the county jail, he says.

Lascaze describes his initial experience at Valley Street as disorienting.

“It’s like looking at a dance floor with the light from above changing all the time,” he says, describing the psychological weight of learning to fit into a new and sometimes harsh environment.

He was placed in a housing unit, or “pod,” at Valley Street, where correctional officers have direct, face-to-face interactions with multiple prisoners.

“If you had violent charges or more serious offenses, they put you in a specific pod, nicknamed ‘Gladiator School,’” he says. Because Lascaze had Class A felonies for robberies and gun charges, he was required to enter a pod with others convicted of first-degree murder and armed robbery. “I went there, and it was all about natural order and survival of the fittest. That’s all it was.”

At Valley Street Jail, Lascaze recalls correctional officers arbitrarily calling room searches during phone hours that would result in lost time speaking with friends and family on expensive phone lines (three dollars for ten minutes at that time), and he believes this type of treatment was intentional. When speaking with family from jail in those early days, he says, “You might be having a disagreement or an emotional conversation with loved ones and then you have to hang up and you leave behind your support system and head back to survival mode.”

The exterior of the Reception & Diagnostic (R&D) Unit at the State Prison. Photo by Tom Jarvis

Brown, who represented Lascaze after he was transferred to the state prison system, says she has had clients at Valley Street who asked for a deal to go to the state prison because of their perception of the county jail.

“I’ve had multiple cases where people have refused county jail time there so they can be sent to the state prison,” Brown says.

Lascaze made a plea arrangement while at Valley Street because he was told by his public defender at the time that if he did not take a deal, he would be “doing more time than I’d been alive at that time.”

Following a plea arrangement, Lascaze was transferred to the New Hampshire State Prison for Men (NHSP) in Concord where he went through the intake process at R&D and learned to adapt to a new environment again.

“Just when you’re adapting to all of that trauma – that type of jungle or lifestyle – you’re getting put into another one as a young adult,” he says, adding that at that time there were no alternative solutions. “Now there are diversion programs, but [at that time] there was no in-depth analysis, no one asking, ‘what is causing Joseph to behave this way?’ It was born out of a tough-on-crime mentality.”

The R&D Process and Housing at the State Prisons

In the R&D unit of the NHSP – and on a smaller scale at the women’s prison – staff perform an intake and a security assessment to determine what medical or other services prisoners need and what programs they will be eligible for.

The intake process involves a thorough body search for contraband, as well as photographs and fingerprints. All property and money on the person at time of arrival is placed in storage for safekeeping and a property receipt is issued to the inmate. The inmate also receives a copy of the correctional handbook, bedding and toiletries, an identification card, and state-issued prison clothing.

Upon completion of the intake process, the inmate is isolated from the other prisoners in a quarantine status for 30 days, with some exceptions. During those first 30 days of incarceration, the prisoner is interviewed and tested by a multidisciplinary team of prison staff and receives classification for their custody level based on the intersection of public risk and institutional risk.

“I’ve known people who have gotten stuck in R&D longer than 30 days, which is particularly unfortunate because it is clearly not designed to hold people long-term,” says Meredith Lugo, a lawyer at New Hampshire Public Defender for more than 20 years. “People want to get out of there as quickly as possible because they are quarantined and not allowed visitors. It’s certainly the worst place to have a client – they are not allowed in the visiting room and not subject to the regular visiting schedule – so, we are sort of at the mercy of calling and hopefully getting permission to visit them in the R&D building.”

The custody levels for inmates range from C1 to C5, with C5 being the highest level of security. C3 is the general population of the prison, and where new inmates are generally housed.

“Some individuals are never going to be able to go below C3 just because of the seriousness of the crime they were convicted of – no matter how good their behavior,” Lugo says.

C5 is reserved for dangerous or problem inmates. The C5 inmates spend all but one hour per day in the Secure Housing Unit (SHU), which is colloquially known as Solitary Confinement. C4 inmates were previously C5 but are working their way back to C3. C2 inmates are housed in a minimum-security facility just outside the prison. C1 classification is for inmates on work release and who are allowed to live in transitional housing units as they prepare for re-entry into the community.

If it is determined that an inmate has a documented history of assaulting staff or other inmates in the county jails, has previously escaped from a secure facility, is sentenced to life without parole, or has documented protective custody issues, they will be assigned to the SHU, where they are separated from the general inmate population. Inmates requiring constant medical or psychiatric care are assigned to either the health services center or the Secure Psychiatric Unit (SPU), respectively.

“SPU is complicated because it’s not just inmates who are housed there,” Lugo says. “SPU also has persons found not guilty by reason of insanity – if they are found to be sufficiently dangerous – and some individuals who are not involved in the criminal justice system at all.”

The latter group – those who have never been charged with a crime – are committed through a probate court but deemed too dangerous by the New Hampshire Hospital, Lugo says. She explains these cases would be a whole other series because they are a subject of litigation.

“[These cases involve] the State housing some people behind the walls of a prison that have never even been charged with anything,” she says.

Prisoners Display a Range of Emotions

Brown says many of her clients over the years, who may have had episodic bad behavior, have never been in the criminal justice system before.

“I’ve represented thousands, probably tens of thousands of people,” Brown says, explaining that as a public defender her case load would sometimes include 80 or 90 people at a time. “It’s rewarding to sometimes keep people out of the grasp of the government when I can.”

But when that doesn’t happen, and her clients are sentenced to prison time or are already serving in the county jails, Brown says she has seen a range of emotions come out.

“I’ve seen everything. I’ve had clients who are just emotional wrecks, crying, frightened, not sleeping because they’re afraid to sleep,” she says. “Sadly, it depends on how much experience the person has with the criminal justice system.”

Brown explains that for some people, the terror of prison is compounded by mental illness or withdrawal from drugs.

“I will say the jails have gotten better,” she says. “They’ve finally realized that when someone is withdrawing from serious drugs, they have to have a protocol for how they handle medications and how the person is treated.”

Two Crimes, Years in Prison

Evenor Pineda, 41, and Tony Hebert, 39, were relatively young when they entered New Hampshire’s correctional system. Their initial experiences, while sharing similarities, are also different.

Pineda, a first-generation American from Nashua, was 23 when he was arrested in 2005 for manslaughter. At the time, he had two young children and says he was at a fork in the road in his life. Pineda was no stranger to the streets or the correctional system, having spent a lot of time as a teenager with a local gang, as well as a short stint in the early 2000s at Valley Street Jail when minors were considered adults.

“As my kids began getting older, I started tapering off from that life – but I still had those connections on the streets,” Pineda says. He recalls the day a fistfight over drugs with someone he considered a friend led to a fatal stabbing and 15 years of prison time. “I stabbed him, and he passed away. It was one o’clock on Sunday. By seven that night, I was arrested. I was arraigned in the morning and sent to Valley Street, where I stayed for one year and 10 days before going to Concord.”

Pineda says his experience with the system prior to entering the NHSP, which included 22-hour lockdowns with two hours for “rec time,” initially led him to embrace the gang affiliations he had adopted earlier in life.

“In the prison system, the gang is very present, and I gravitated back to what I was most familiar with,” he says, explaining the relief and comfort he felt going to prison after getting out of Valley Street. “All the rumors of excessive force by COs used at Valley Street were true. I remember waking up in the middle of the night to a grown man screaming because he was getting beat up by an officer – or more likely, officers.”

Pineda met Hebert at the NHSP in 2014. Hebert was convicted of manslaughter a year prior, following an altercation in July 2011 that led to the shooting death of a young man in Manchester. Hebert had served two and a half years at Valley Street before receiving a sentence of 14 to 30 years at the NHSP.

Pineda, who had experience with the system, says he put his head down and prepared for a new identity without his children or his friends when he entered the prison. Hebert, meanwhile, had no such experience, making the transition much more difficult.

“I was shocked, and it was an out-of-body experience,” Hebert says, explaining that his initial experience of prison came with a lot of guilt – over the price both the victim’s family and his own paid for his crime – which still weighs on him. “But those first few minutes, I was in complete disbelief.”

In his two and a half years at Valley Street, Hebert had seven public defenders before he struck a deal.

“My lawyer told me: ‘You’re a young black man in the state of New Hampshire, and you’re accused of a violent crime with a firearm. You should take the deal,’” he says. “After being at Valley Street for that long, I didn’t care. ‘Just get me out of here,’ I thought.”

After leaving Valley Street, Hebert was sent to a Closed Custody Unit (CCU) at the NHSP following his initial time in R&D.

“I was nervous because it was a long time and I have a wife and three kids,” he says. “I was also thinking, ‘this is what I’ve been dealt, and I need to do my time and try to get past this the best I can.’”

Hebert eventually made it to C3, or “general population,” where most inmates are housed at the NHSP.

“In CCU, they watch you for observation for a few months,” he says. “So, I thought, ‘Let’s try to make the best of this.’”

For the next 12 years, moving between various units until his release in June 2023, that’s what Hebert did.

Moving Forward in Prison

Lascaze, Hebert, and Pineda all concur that the initial days and months in jail and prison involved a lot of compartmentalization.

“Compartmentalizing is a survival technique people use to differentiate the inside and the outside,” Pineda says. “Everyone wears masks on the outside, but on the inside, you wear a thicker mask to protect yourself. Everyone has their chow-hall face.”

All three men agree that letting one’s guard down happens over time, but it’s difficult.

“For me, the motivation was that my wife was visiting with my kid saying, ‘Daddy, Daddy, Daddy,’” Hebert says. “There’s a big difference between trying to balance family life and navigate the prison system, but that meant more to me than any of the nonsense that came with the prison system.”

The next few articles in the NHBA Prison Series will focus on life in prison, following Joseph Lascaze, Evenor Pineda, Tony Hebert, and others through their experiences with the New Hampshire State Prison system.